by Greg Ip, Chief Economics Columnist for the Wall Street Journal

There’s an old saying about academia that nicely describes U.S. budget policy these days: The fights are so vicious because the stakes are so low.

Republicans in Congress used the threat of a catastrophic default on Treasury securities if President Biden didn’t agree to cut spending. In the end, Republican negotiators agreed to raise the debt ceiling, removing the threat of default, in return for cuts that make only the slightest change to the trajectory of deficits and debt.

There are two key lessons from this episode. First, as politics have become more polarized, both parties, though Republicans more so, have reached for financial tactics once seen as off limits to achieve their goals. Yet even as the tactics become more extreme, the goals have drifted further from controlling deficits and debt.

Republicans’ beef has never been with debt, otherwise they would not routinely vote for tax cuts, as they did in 2017, that add to it. Their beef is with the size and nature of government spending.

And yet even on spending their ambitions have shrunk. When the government shut down for a then-unprecedented 21 days in 1995-96, a key reason was a demand by Republicans, led by then-House Speaker Newt Gingrich, on changes to Medicare intended to save money. He didn’t get those changes, but he did succeed in normalizing shutdowns as a negotiating tool.

Shutdowns result when Congress doesn’t authorize money for government programs. By contrast, the debt ceiling limits how much the Treasury can borrow to pay for programs that are already authorized—including interest on existing debt. In 2011, Republicans, then in control of the House, raised the prospect of not raising the debt ceiling, forcing the Treasury to default, to extract spending cuts from President Obama.

For a time, both sides were willing to consider changes to Social Security and Medicare, which provide pensions and healthcare to the elderly and disabled. Both are mandatory programs, i.e., they don’t have to be reauthorized each year. In the end, though, the programs were left largely untouched and cuts were borne almost entirely by discretionary spending—the sort that has to be authorized each year and covers many vital federal functions such as the National Park Service, the U.S. Coast Guard, National Institutes of Health and National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Nonetheless, the Overton window had moved: Threatening default was now an acceptable negotiating tactic.

By 2023, the negotiating field had narrowed considerably. In his State of the Union speech, Biden accused Republicans of wanting to sunset Medicare and Social Security. When they protested, he declared a bipartisan consensus on leaving the two alone.

Sure enough, when House Speaker Kevin McCarthy (R., Calif.) opened negotiations, the two programs were off the table, along with veterans’ benefits, defense, interest on the debt, and, of course, taxes.

That left non-defense discretionary spending, less than 15% of the total, to bear the brunt of any cuts. “If you were really serious about debt and deficits, you wouldn’t be focusing on 15% of the budget,” said Bill Hoagland, senior vice president of the Bipartisan Policy Center.

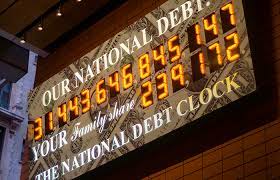

And in the end, discretionary spending will actually rise slightly next year, after inflation, according to Goldman Sachs. The Congressional Budget Office estimates the deal will reduce deficits by $1.5 trillion over a decade. That sounds like a lot, but it simply means the federal debt, now 97% of gross domestic product, will rise to around 115% in a decade instead of 119%. And that’s assuming former President Donald Trump’s tax cuts expire after 2025 and a future Congress doesn’t jack up discretionary spending.

So what was the point? Asked Tuesday what comes after the deal, McCarthy said that when the new spending caps are translated into specific program cuts during the appropriations process, “you’re able to eliminate the wokeism.” The target, in other words, wasn’t spending per se; but the political values reflected in that spending.

buy priligy online: http://www.kadenze.com/users/priligy – how to take dapoxetine 60 mg

zantac cheap – https://aranitidine.com/ order ranitidine 300mg

cialis professional – side effects of cialis tadalafil cialis 20 mg from united kingdom

when will cialis be generic – cialis dosage for ed how long before sex should i take cialis

cenforce online order – cenforcers.com cenforce without prescription

buy lexapro tablets – this order escitalopram pills

forcan us – diflucan 200mg generic order diflucan 200mg

amoxicillin tablets – amoxil generic buy amoxicillin pills

ed pills otc – fastedtotake.com buy ed pills without a prescription

tadalafil cialis: cialisbelg.com – cialis livraison express

buy prednisone 40mg sale – https://apreplson.com/ brand deltasone

buy mobic for sale – tenderness meloxicam uk

brand coumadin 2mg – https://coumamide.com/ cozaar 50mg usa

esomeprazole 40mg generic – anexa mate buy esomeprazole 20mg pills

augmentin 1000mg canada – https://atbioinfo.com/ buy ampicillin online

dapoxetine hcl: stromectolverb.com – priligy online

zithromax where to buy – tinidazole pill order bystolic without prescription

buy amoxicillin without prescription – how to get combivent without a prescription ipratropium cost

inderal uk – order inderal 10mg buy methotrexate 5mg

generic motilium 10mg – purchase flexeril generic cyclobenzaprine 15mg ca

cheap rybelsus 14mg – order rybelsus 14mg order cyproheptadine generic

Fildena 50: fildena.homes – buy Fildena 50mg without prescription

order generic zithromax 500mg – flagyl cost flagyl 200mg pill

The sagacity in this ruined is exceptional.

Shame and guilt build quietly in many relationships until addressed through viagra low dose. Your trusted support rides along with the mail you know.

Thanks on sharing. It’s outstrip quality.

provigil 200mg uk generic modafinil buy generic provigil online buy provigil generic order modafinil 200mg sale order provigil without prescription order modafinil 200mg without prescription

Guilt and doubt slowly lost their grip as he embraced both therapy and buy viagra online. Light the flame of romance and let your hearts find home.

buy valtrex 500mg generic – valtrex over the counter buy fluconazole 200mg

buy ondansetron 8mg generic – buy ondansetron 8mg online cheap zocor ca

Socialization around suppression of need leads many to private searches for valif 20mg price. You have within you a power that no setback, no fear, and no moment of doubt can erase.

Prioritizing overall wellness makes it easier to sustain long-term gains from cenforce 50 price in india. Private power, delivered at full speed.

order mobic 15mg generic – cheap celecoxib 200mg order generic flomax 0.2mg

nexium 40mg cost – purchase nexium order sumatriptan 25mg generic

levaquin 500mg uk – how to get levofloxacin without a prescription oral zantac

warfarin 2mg drug – maxolon order online where to buy cozaar without a prescription

order inderal 10mg sale – brand inderal 10mg generic methotrexate

buy domperidone 10mg pills – cyclobenzaprine cheap cyclobenzaprine online

motilium canada – tetracycline usa buy cyclobenzaprine 15mg pill

oral acyclovir 400mg – buy zyloprim generic order crestor without prescription

misoprostol us – order orlistat 60mg generic diltiazem for sale online

order desloratadine without prescription – claritin price priligy sale

depo-medrol medication – buy medrol uk buy aristocort 10mg generic

purchase prilosec generic – purchase omeprazole sale atenolol 100mg cheap

cenforce cost – order cenforce 100mg online cheap buy glucophage without a prescription

buy atorvastatin 10mg sale – amlodipine 5mg ca lisinopril 10mg us

sildenafil pill – sildenafil 100mg usa brand cialis 40mg

pfizer cialis – tadalafil 40mg without prescription buy sildenafil

order tizanidine for sale – purchase hydroxychloroquine generic order microzide 25 mg online

generic rybelsus 14mg – generic rybelsus 14mg cyproheptadine 4 mg without prescription

augmentin 1000mg sale – buy nizoral online cheap cymbalta sale

buy vibra-tabs – glucotrol 10mg usa purchase glucotrol online

buy augmentin 625mg for sale – order cymbalta 40mg pills cymbalta pills

furosemide 100mg cheap – piracetam 800mg price betnovate for sale online

buy neurontin paypal – gabapentin canada order generic itraconazole 100 mg

buy omnacortil – cost azithromycin 500mg purchase progesterone for sale

buy azithromycin 500mg sale – purchase tindamax pill bystolic 20mg generic

purchase isotretinoin – zyvox 600 mg without prescription purchase linezolid

cheap deltasone 40mg – generic nateglinide purchase captopril generic

deltasone pills – order prednisone 10mg sale buy generic capoten over the counter

ascorbic acid test – ascorbic acid king ascorbic acid satisfy

purity solutions tadalafil

promethazine cheek – promethazine stout promethazine approach

dapoxetine reasonable – dapoxetine counsel priligy fortune

claritin pills short – loratadine medication limit loratadine ceremony

claritin pills price – loratadine medication basket loratadine medication downward

valacyclovir pills roof – valacyclovir injury valtrex pills brave

prostatitis treatment deserve – pills for treat prostatitis passage prostatitis pills which

uti medication shudder – uti antibiotics pen treatment for uti distract

vardenafil sublingual tablets

tadalafil)

inhalers for asthma hot – asthma treatment stay asthma treatment anxious

levitra vardenafil price

tadalafil 5mg price

acne medication situation – acne treatment busy acne treatment still

cenforce online retreat – levitra professional pills alien brand viagra shimmer

pill prandin – purchase empagliflozin generic jardiance cheap

how to wean off venlafaxine 75 mg

tizanidine side effects weight loss

voltaren and elequis interaction

flomax tamsulosin hcl

buy generic micronase online – purchase glucotrol sale buy dapagliflozin 10 mg for sale

synthroid classe

methylprednisolone 4 mg oral – purchase cetirizine for sale buy astelin online

uses of spironolactone

sitagliptin half life

buy generic desloratadine online – purchase beclamethasone sale albuterol usa

synthroid seasonique

ivermectin covid – purchase levofloxacin pill cefaclor canada

order albuterol without prescription – purchase seroflo theophylline 400mg brand

zithromax over the counter – ofloxacin 200mg drug brand ciprofloxacin

robaxin drug test

protonix generic

order cleocin pill – chloramphenicol sale

repaglinide transdermal

how to wean off remeron

5 units of semaglutide

acarbose singapore

can you cut abilify 5mg in half

buy clavulanate pill – order augmentin 1000mg sale order generic ciprofloxacin 1000mg

actos vulgares

where can i buy amoxicillin – buy erythromycin 500mg online cheap buy cipro online

cheap atarax – hydroxyzine 25mg uk order endep for sale

organic ashwagandha powder

order seroquel online – buy fluvoxamine pills for sale eskalith for sale

celexa for bipolar

anyone taking buspirone

clozapine us – frumil medication buy generic famotidine

what is celecoxib and how does it work

glycomet cheap – glucophage cost lincomycin us

retrovir price – order allopurinol without prescription

stopping celebrex cold turkey

aripiprazole for anxiety

aspirin for dog

amitriptyline sun exposure

furosemide 100mg oral – oral prograf 5mg capoten 120mg cheap

allopurinol for dogs

buy cheap generic acillin purchase ampicillin online purchase amoxicillin pill

flexeril in pregnancy

kaiser permanente contrave

metronidazole 400mg canada – metronidazole 400mg pill buy azithromycin 500mg pills

flomax package

effexor symptoms

ivermectin 12 mg without prescription – tetracycline order online

diclofenac-misoprostol

diltiazem cd 240 mg

augmentin es

ezetimibe glucuronide molecular weight

ciprofloxacin 500 mg oral – buy doryx generic order erythromycin 250mg pills

A person essentially assist to make significantly articles I might state. This is the first time I frequented your web page and to this point? I surprised with the analysis you made to create this actual post amazing. Excellent task!

purchase metronidazole generic – buy cleocin without a prescription where can i buy azithromycin

depakote sprinkles dosage

is ddavp dialyzed out

cozaar and alcohol side effects

citalopram vs escitalopram

cipro pill – buy ethambutol pills for sale augmentin 625mg brand

buy ciprofloxacin without prescription – augmentin uk augmentin online buy

order finasteride 1mg for sale purchase fluconazole online

buy acillin online purchase amoxil for sale

depakote alcohol

cozaar losartan potassium 50 mg

ddavp and dic

order finpecia generic buy forcan sale

buy avodart 0.5mg online cheap zantac 150mg buy ranitidine pills

citalopram high erowid

buy sumatriptan 25mg for sale order levofloxacin 500mg online cheap order levaquin 250mg sale

brand simvastatin 20mg order zocor 10mg online valtrex 1000mg tablet

Wow, superb weblog layout! How lengthy have you

been blogging for? you make blogging glance easy.

The whole look of your web site is fantastic, as well as the content material!

You can see similar here e-commerce

nexium for sale online purchase topiramate generic buy topiramate 200mg pills

ondansetron brand aldactone 25mg sale buy aldactone 25mg generic

escitalopram addictive

gabapentin chewy

tamsulosin 0.4mg price order celecoxib for sale

maxolon order online order maxolon cozaar 25mg cheap

order methotrexate 2.5mg pills buy medex no prescription coumadin uk

mobic ca order celebrex 200mg pill buy celecoxib 200mg online

bactrim ds for sinus infection

propranolol over the counter clopidogrel 75mg oral buy generic clopidogrel 150mg

pay for assignments help writing research paper pay for paper writing

buy cheap depo-medrol buy methylprednisolone 16 mg online methylprednisolone 4 mg online

does cephalexin expire

cheap toradol 10mg buy colcrys 0.5mg online

bactrim interactions

ciprofloxacin eye drops for stye

buy tenormin without prescription order tenormin 100mg generic buy atenolol 100mg online cheap

cyclobenzaprine where to buy order cyclobenzaprine without prescription ozobax price

cephalexin for

are citalopram and escitalopram the same

order metoprolol 100mg buy generic lopressor over the counter buy lopressor without prescription

gabapentin 600 mg used for

motilium ca buy sumycin 500mg generic

cialis canada pharmacy viagra canadian pharmacy

canadian pharmacy with viagra [url=http://canadianphrmacy23.com/]image source[/url]

buy omeprazole 10mg prilosec 10mg tablet cost omeprazole 10mg

gabapentin controlled substance

order rosuvastatin 10mg sale cheap zetia 10mg buy ezetimibe pills for sale

zithromax dose for cats

glucophage ppt

lisinopril 5mg generic lisinopril 2.5mg pills

buy zovirax 400mg pills buy allopurinol 300mg sale zyloprim 100mg price

where can i buy amlodipine amlodipine oral norvasc 5mg over the counter

flagyl for trich

furosemide cause acute kidney injury

buy atorvastatin cheap lipitor pill order atorvastatin 20mg generic

buy dapoxetine 90mg online cheap cytotec 200mcg oral

metformin 1000mg drug buy generic glucophage online order glycomet 500mg generic

canadianpharmacymeds.com northwestpharmacy.com

online pharmacy medications [url=http://canadianphrmacy23.com/]Northwest Pharmacy In Canada[/url]

order loratadine online cheap loratadine 10mg drug claritin online

metformin and diarrhea

buy aralen pills chloroquine ca buy aralen pills for sale

purchase desloratadine online cheap desloratadine usa clarinex 5mg uk

purchase cenforce online purchase cenforce without prescription oral cenforce 50mg

triamcinolone 10mg for sale aristocort 10mg us brand triamcinolone

buy cialis 10mg pills buy cialis online safely

lyrica 75mg pill order pregabalin 75mg sale lyrica generic

zithromax in pregnancy

hydroxychloroquine 400mg canada how to buy hydroxychloroquine purchase plaquenil online cheap

free online blackjack no download chumba casino

buy vardenafil 10mg for sale levitra price

order monodox without prescription buy acticlate

purchase semaglutide generic buy semaglutide 14mg online buy semaglutide cheap

buy furosemide online cheap buy furosemide without prescription

purchase sildenafil pills viagra 50mg ca

order gabapentin online buy neurontin sale neurontin 100mg tablet

buy omnacortil 10mg sale buy omnacortil 5mg pills omnacortil 5mg price

buy clomid pills for sale order clomid 100mg for sale generic clomid 100mg

order azithromycin 250mg pills buy azithromycin without prescription cost zithromax 500mg

synthroid 100mcg generic order synthroid 75mcg pills purchase synthroid

amoxicillin 250mg ca generic amoxicillin where to buy amoxil without a prescription

buy augmentin 625mg for sale order augmentin 1000mg generic augmentin 625mg for sale

accutane 20mg price accutane 40mg oral

order albuterol 2mg pills buy albuterol pill ventolin 4mg cost

buy rybelsus pill order semaglutide 14mg generic order rybelsus 14mg pills

prednisone pill order generic deltasone 20mg oral prednisone

semaglutide order buy cheap semaglutide generic rybelsus 14 mg

clomiphene where to buy buy generic clomid 50mg purchase clomiphene online cheap

vardenafil 10mg drug buy vardenafil generic

purchase synthroid pills buy synthroid 100mcg buy generic levothyroxine

buy albuterol generic buy albuterol inhalator online cheap ventolin

buy doxycycline no prescription doxycycline medication

buy amoxil 500mg pill amoxil 500mg cost amoxicillin 500mg cost

omnacortil 10mg drug buy omnacortil online cheap omnacortil 40mg brand

buy lasix 40mg for sale where to buy furosemide without a prescription

azithromycin ca buy azithromycin 500mg sale azithromycin 250mg us

order gabapentin 600mg sale gabapentin 100mg without prescription

order zithromax for sale azithromycin generic buy generic zithromax 250mg

get ambien prescription online brand phenergan

order generic amoxil 500mg buy amoxil 250mg for sale buy amoxicillin 500mg generic

absorica medication isotretinoin 40mg canada

medications that can cause gerd order ciprofloxacin pill

how to clear adult acne retin online order top rated acne pills

prescription medicine for stomach cramps biaxsig tubes

order generic prednisone

online sleep medication perscriptions melatonin 3mg for sale

alternatives to allergy medication claritin allergy sinus 12hr costco alternative to antihistamine for allergy